Derrick Greaves first came to prominence in the mid 1950s as a "Kitchen-sink" painter. However, from the outset, the 'Kitchen-Sink' painters or 'Beaux Arts Quartet', as Derrick Greaves, John Bratby, Edward Middleditch and Jack Smith were also known, were grouped by expediency, not ideology. True, they studied at the Royal College and exhibited at the Beaux Arts Gallery, but there was no shared aesthetic or common manifesto.

As stated by Helen Lessore in 1951: "It should be stressed that they themselves never had any intention of forming a group, nor of inscribing themselves under any particular faction The more one studies these four young painters, the more different they appear. One has to take the trouble to appreciate individuals individually. Short cuts by classification are superficial".

If they shared anything then it was a suspicion of elegance and a dismissal of Henry Tonks and Randolph Schwabe's legacy of polished drawing that had taken root at the Slade School of Fine Art. Instead, their aesthetic was tougher and more robust, exemplified by their preference for charcoal rather than pencil to give a greater forthrightness and engagement: 'We were all discontented, kicking against the pricks. The bit was too tight on the drawing. We wanted to be free.the exception of John Bratby, whom Greaves barely knew and seldom met, there were bonds of personal friendship. From 1949-52, Greaves lived in Earls Court at 44 Pembroke Road, a house that had belonged to Aubrey Beardsley's mother, with friends from Sheffield including the painters Jack Smith and Leslie Duxbury as well as the sculptor George Fullard. This was extremely enterprising: since the building had been bombed, Greaves and his fellow students were able to secure a long lease on condition that they restored the property. One of his most powerful early paintings, Baby in Pram (1949) showed Duxbury's child on the doorstep and a portrait of Jack Smith (c.1949) was also painted there.

Jack Smith had been a friend since childhood when both lived on the same Sheffield street and shared a love of painting and drawing. Then, when both men went to live and study in London, it was natural that they should share digs together. Greaves recalls that Jack Smith had the large back room at Pembroke Road, overlooking the garden, and worked so conscientiously that soon the room was so filled with paintings on board that Smith could barely get to his table to eat. It was a fun and stimulating time. Greaves was particularly close to George Fullard whom he recalls as very bright, rather wild and with a lightning mind. He was full of songs and jokes and for entertainment on a Friday and Saturday evening Greaves and Fullard would go down the street to the Pembroke Arms pub and sing music hall songs such as Me and Jane in the Plane, The Winkle Song and Me and Old Bill Smith were Dusties.

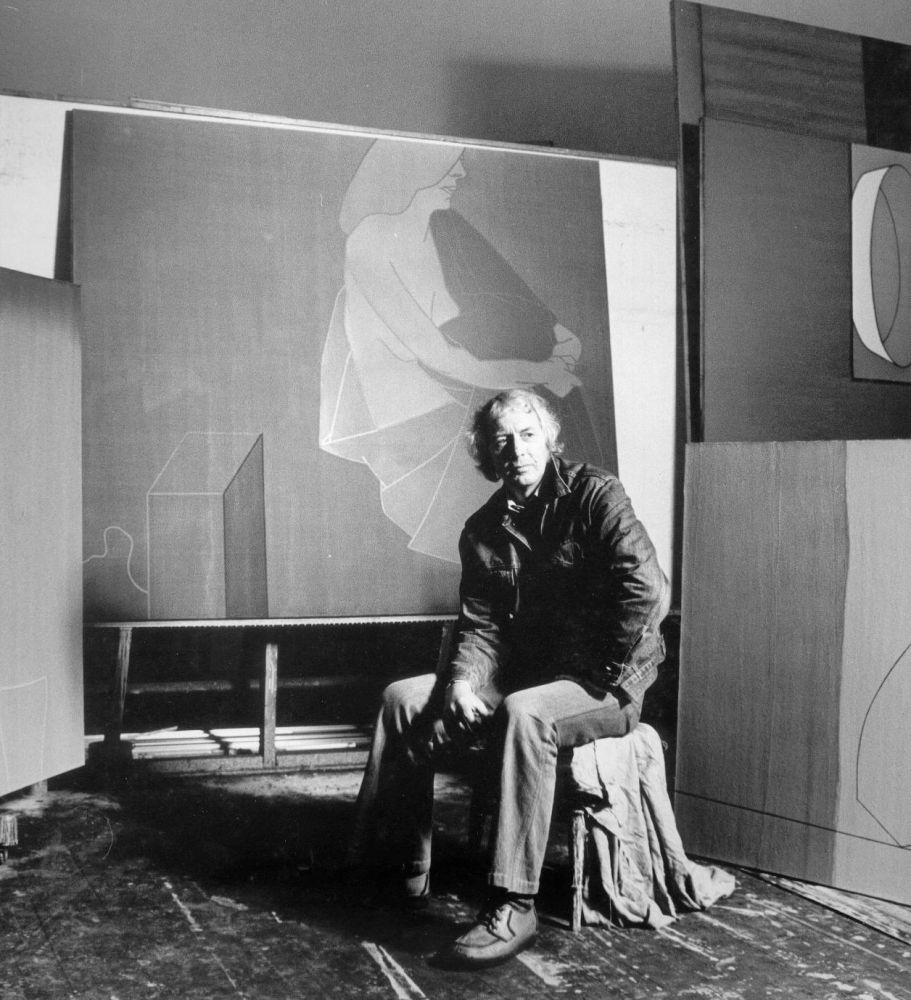

[Fawcett Yard Studio Interior]

Around the corner was Edward Middleditch's studio and his close friendship with Greaves dates from this time. They would see each other's work as it progressed, talk intensively about their interests and read many of the same authors, among them Jean-Jacques Rousseau, D.H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley. Dissatisfied with the work of many of their contemporaries, they sought an art that was tougher and more straightforward. This led them to reject Paris, or at least its younger artists, whom they felt to be imitating the mannerisms of their elders. But their conversation was above all practical rather then theoretical; for example, conversations about paint and colour might turn to their preference for Rembrandt colours, which had a greater range than was offered by the more familiar Windsor and Rowney.

Where Middleditch and Greaves differed was in their response to landscape, a dominant concern for both artists, neither of whom dwelt on city motifs. Greaves loved the romantic idea of the northern landscape, running through Wordsworth's Cumbria to W.H. Auden's idea that you can put your ear to the ground and hear water in unseen conduits. In contrast, Middleditch responded to the landscape in more visual terms, not least through his friendship with some of David Bomberg's former students who dramatised the bulk of the landscape and the drama of a slope.

Above all, there was a generosity of spirit, a camaraderie in which these artists were more inclined to praise than criticise. What mattered was to do the work. Touting the work around galleries was anathema and the idea that it might sell a distant thought. If there was a 'Kitchen-Sink' group then it was this band of artists living together from 1949-52 in a house of bed-sitters with a shared sink in the kitchen downstairs. This was a period that predated their first one person shows and coincided with their student years, and it is conspicuous how little this circle of artists ever had to do with John Bratby. What's more, by the time that 'Kitchen-Sink' painting was championed Greaves was not even living in Britain, having won a scholarship to study for a year at the British School in Rome (1952-3), which he then succeeded in extending for a further year (1953-4).

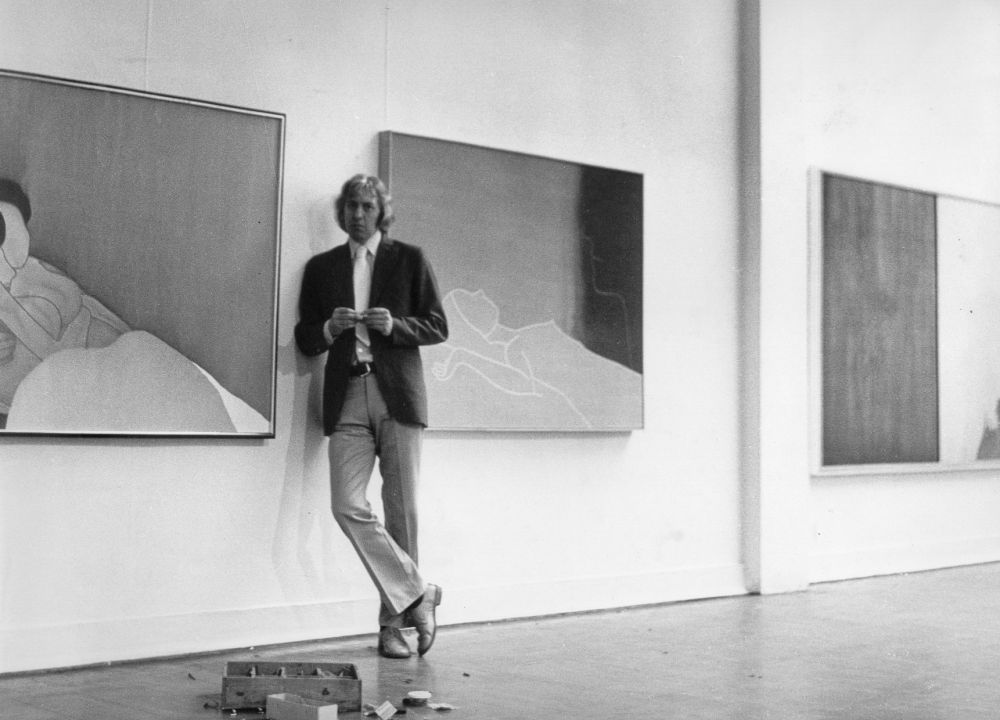

[Jack Smith, Edward Middleditch, John Bratby, Helen Lessore and Derrick Greaves 1956]

In fact, the critical promotion of a 'Kitchen-Sink' school developed during the mid rather than the early 1950s. In late 1953, the Walker Gallery in London staged an exhibition entitled Paintings for the Kitchen. Just as John Berger presented young social realists as a continuation of tradition, so the anonymous reviewer of this exhibition in Art News and Review provided an historical foundation: the kitchen has a hallowed place in the history of art ... The marmites of Chardin, the flayed chickens of Soutine, the eggs and frying pans of William Scott, are all part and parcel of the great mythology of European art.year later, David Sylvester wrote an essay entitled 'The Kitchen-Sink' for the recently launched journal, Encounter. This, too, provided an historical context for the paintings of a new generation of artists and again addressed painters from across Europe. Sylvester's essay was extremely broad in its historical and geographical references. It used 'Kitchen-Sink' as a characterisation, not as a label, to trace a broad international trend rather than denoting a small British group and did so without making claims for the realism of these painters. Indeed, the very idea that 'Kitchen-Sink' painting constituted realism was anathema to Sylvester, whose own existentialist 'realism of the imagination', exemplified by Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti, stood in opposition to the 'Romanticism' that he deplored in artists such as Paul Rebeyrolle. However, the label 'Kitchen-Sink' stuck and was subsequently applied to just four artists - Bratby, Greaves, Middleditch and Smith - at the centre of claims for a British social realism and Sylvester became credited with giving the quartet its name.

Despite Sylvester's perceived association with the idea of 'Kitchen-Sink' painting, the presentation of a quartet owed more to other writers, not least to John Berger, John Minton and Helen Lessore of the Beaux Arts Gallery. Lessore not only staged the first solo shows for the painters but also arranged their first group show, at Cambridge's Heffer Gallery in 1955, which encouraged critics to seek points in common in what became known as the Beaux Arts Quartet. Their profile helped Lessore's gallery assume a coherent identity and it quickly became synonymous with social realism by young artists. In 1953 John Berger asserted that 'The Beaux Arts is quickly and deservedly gaining the reputation of being the one gallery where it is possible to see the serious work of young painters'; in 1956 Quentin Bell observed that 'the Beaux Arts Gallery ... is in a sense the spiritual home of social realism in this country' and, in 1957, Trewin Copplestone described the gallery as the 'group Headquarters' for the Kitchen-Sink painters.

In fact it was not until the 1955 exhibition of the Beaux Arts Quartet at Heffer Gallery, followed a year later by the Venice Biennale, that Bratby, Greaves, Middleditch and Smith were exhibited together as a group. In each case, however, the stress was placed on the individuality of each artist. Indeed, despite the desire to champion a common project, John Berger was sophisticated in the way in which his first reviews of the Beaux Arts Quartet not only placed the work of each artist in a wider national and international context but also acknowledged individual achievement. In a review of Bratby's first solo show at the Beaux Arts in 1954, Berger contextualised the 25 paintings on show, writing that 'Bratby's vision has values and qualities in common with Jack Smith, Edward Middleditch and Derrick Greaves. There is the same suspicion of elegance and the same ability to be moved by the commonplace'. However, he did also acknowledge its 'intense and personal emotions'.

Certainly, Berger made generalisations about the social implications of the quartet's choice of subjects, but nevertheless he was careful to distinguish between intention and implication. Recognising that 'the motives are not directly social or political', Berger argued that 'they all paint without protest but with great sympathy for the few precious possessions of the dispossessed'. The consistency he perceived in their subject matter encouraged Berger to believe that the quartet did not simply present what was in front of them but had a conception of what was an 'appropriate' subject.

A prevalent theme was that of a mother and baby. Reflecting both personal circumstances and a post-war baby-boom, these prosaic images were nonetheless an antidote to Henry Moore's lofty idealisation of the subject as a universal symbol of maternity. Edward Middleditch's rare depiction of a person, Baby (1952), Jack Smith's iconic Mother Bathing a Child (1954) and Greaves's First Steps (1956) are paintings of privation conveyed in muted tones that are at best distantly related to Moore's well-fed families. Greaves had married a nurse, Margaret Johnson in 1950 and in 1956 she gave birth to their first child, Simon, soon to be followed by Julia and Daniel. Images of his wife and oldest son would dominate his work of 1956 and its presentation in exhibitions in London that year.

However, critics were quick to recognise the fissure between critical aspiration and artistic practice, which was growing ever wider as the work of the individual members of the Beaux Arts Quartet became more subjective, hermetic, romantic and even abstract. Their former tutor at the Royal College, John Minton, who perhaps felt that their fame was eclipsing his own, satirised this in an essay of 1956 entitled 'Three Young Contemporaries'. Referring to 'three of the most notable painters who have left the Royal College in recent years', namely Greaves, Middleditch and Smith, to whom he referred by initials only, Minton ridiculed the gap between the lofty aspirations of the critic and the pragmatic concerns of the artist:

No painter wears his heart on his sleeve and no painter explains himself except by his painting. Set a questionnaire he will do everything to lose it ... Is that the ageless Venice, Mr. G? Are you a social realist, Mr. M? Is that the Child of Europe, Mr. S? ... Is it valid? Does it relate? Is it socially significant? The critics cry and in answering themselves fill their columns. Giving the painter time to get the nose drawn right, the foot reshaped, the foreground redrawn, the middle-distance reconsidered. Yes, but isn't it too descriptive? Or not descriptive enough? Or too theatrical? No, but I mean, is it timeless? And the painter has time to buy more paints, to catch the train, even for a short delay in the station bar, and he is away...

Elsewhere their individuality was celebrated. One of the leading British art journals, Art News and Review, published a front page profile on Derrick Greaves in November 1956 that not only confirmed how quickly his reputation had become established but also provided one of the most prescient characterisations of his concerns. In it the art critic Pierre Rouve wrote that:

attachment to whatever the devalued term 'realism' may mean is all too often a shield for creative impotence. With Derrick Greaves it is above all an act of humility. It is the refusal of a man deeply immersed in the vicissitudes of the human adventure to transform his art into some kind of shop window for the wares of egocentric fetishism.

By now Greaves was routinely included in London's institutional and commercial galleries. His first significant exposure had come in group exhibitions of young painters at the Lisle Street gallery of the Left-leaning exhibiting society, the Artists International Association (A.I.A.) in 1949 and 1950; at the R.B.A. Galleries in 1950, where he showed Deal Beach (1949) ; and then at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the seminal group exhibition of social realism, Looking Forward (1952). From such exhibitions Greaves received his first attention from the press.

The most important of these exhibitions was Looking Forward, a manifesto exhibition of social realism curated by John Berger, which was explicitly conceived to attract a large public audience and to be accessible to the working class. As Berger wrote, the exhibition was intended to provide 'the raw material of a socialist art' for which 'the new patrons will be trade unions, democratic local councils, community centres, etc.' The catalogue provided a bold characterisation of Berger's realism:

Realism is not a method but an attitude of mind ... the realist always starts from the particular and from this beginning tries to deduce a typical truth ... the realist is fundamentally optimistic because he accepts the world - not necessarily as it is - but as it can be, according to the potentiality of its own laws of development ... The realist attitude breaks down the studio wall and projects the artist into ordinary life.

The materiality of the thick paint married to social concerns led Greaves and several of his contemporaries to be presented by critics as followers of Gustave Courbet, especially in the wake of a major exhibition of the artist at the Marlborough Gallery in 1953. Prominent among these champions were John Berger and Nevile Wallis. In his review of Berger's exhibition, Looking Forward, Wallis singled out for praise Arthur Hackney, Edward Middleditch and Derrick Greaves, whom he characterised as 'Cousins of Courbet'. This relationship was also at the heart of Berger's praise of artists as individual as Prunella Clough and Josef Herman.

Following Looking Forward, Greaves's public career took off, although characteristically the artist was diffident about this success. In 1953 he had the first of his two solo exhibitions at Helen Lessore's Beaux Arts Gallery. In contrast to Michael Andrews, for whom the gap between being offered a show by Helen Lessore and its realisation was six years, Greaves had just three weeks between Lessore's visit to his studio and the staging of his first show at her gallery. Greaves recalls that she visited twice, explaining that she never decided after a single studio visit: 'then to my terrible surprise she said can you be ready in three weeks? So I showed what I had.' This included canvases he had rolled up and brought back from Rome and recent works of Sheffield. But Greaves never saw the show, having by then travelled back to Italy for the second year of his Abbey Major scholarship in Rome.

Greaves sold everything at his first one person show at the Beaux Arts Gallery. As the artist later recalled:

I was surprised but not amazed at the success, but I was just getting on with things in Italy John Berger wrote about me regularly after that, but it was as though it was happening to somebody else. It's journalism. All painters know what the value of their paintings are. The fact that they may be used to justify this, that and the other is not to do with them really. I felt that you couldn't ever really expect to make a living out of painting and didn't really want to court the publicity. I didn't really know what to do with it. Bratby wanted us to be known as a group, but the rest of us felt the job was to be an individual. Be responsible for your own thing. It all happened in parallel to what I was doing.

Greaves's exhibition attracted enthusiastic support. Stephen Bone, writing in the Manchester Guardian, proclaimed that this was 'one of the most promising first exhibitions that has been seen in London for some time', praising 'a strong and individual personality'. John Russell, meanwhile, declared in the Sunday Times that the exhibition, 'with its ease and natural breadth of manner, foretells a distinguished career'.

Then, from November to December 1955, Greaves held his second show at the Beaux Arts, this time coinciding with Sheila Fell's first exhibition at the gallery. Given the large size of the paintings just eight were shown, accompanied by a portfolio of drawings. Some of his most ambitious paintings, these works were nonetheless attacked in The Times for an 'obsessive concern with detail at the expense - particularly in some large work - of an interrelated design'. This was criticism that John Berger directly refuted in a lengthy paean of praise: 'The privilege - and I mean that in all modesty - of describing these works for the first time presents formidable difficulties; their originality, which manifests itself not in their novelty but in their profound obviousness, excludes all ready references.' What Berger identified and stressed was a literal, mimetic quality, a direct relationship between Greaves's handling of paint and the quality of the thing depicted: from the smoothness of a baby's skin to the roughness of a worker's hands. Arguing that 'Greaves has rejected every precept of academic teaching', Berger praised the way that 'the arbitrariness of any one moment of life comes before the imposed pattern of any composition'. Hence the fact that the largest painting on show, Cart and Peasant, eschews a conventional composition and gives each object its own autonomy and individuality, not so much a breakdown of the composition as a way of showing respect for each distinct element: 'Indeed each object is separate. If a man has only ten possessions, he tends to count them separately.' This separation, already identified in this review of 1955, would be a central aspect of Greaves's presentation of objects in the decades to come.

Inclusion in group exhibitions consolidated Greaves's reputation and status as a leading realist. In 1955, he was included in The Artist's View of an Industry which laid stress on the work of young artists who were invited by Shell Oil to make works on the subject of the oil industry. Greaves and Middleditch each produced pictures of a distillation unit at Shell Haven refinery in Essex, suggesting that the two friends had made a joint visit. Then, the following year, Greaves was one of the younger exhibitors in the Institute of Contemporary Arts (I.C.A.) exhibition of landscape painting (January 1956) and included in the Arts Council's Six Young Painters (1957), which presented figurative paintings by John Bratby, Michael Andrews, Cohen, Martin Froy and Philip Sutton. Internationally Greaves also appeared in major exhibitions in Russia and Italy. Then, at the year's end and coinciding with Rouve's aforementioned profile, Greaves had work included in exhibitions at the Adams Gallery and the Piccadilly Gallery, both in London.

By now drawings and paintings of mother and child had become a key theme for the artist and were brilliantly evoked in an essay by John Berger on the Kitchen-Sink painters that reproduced Greaves's painting, Sleeping Mother and Child (1956):When he paints the hand of a mother holding her child, he tries to suggest all that has made that hand what it is. The cooking, the sewing, the caressing, the clenching in anger, the scrubbing, the way it's been held by her lovers. And then he contrasts all this with the baby's hand - the baby who is just beginning to learn through his hands to distinguish one object from another.

In precise working drawings of the mid 1950s the form would be carried by line alone, as in Baby - Finger in Mouth (1956) , the sparseness of which anticipates the use of line in Greaves's later work. Greaves would convey his tenderness towards the subject, as in Mother and Child (c.1956) by using soft pencil, but he would also make robust pencil and charcoal drawings, such as Baby, Bath and Dog (1956) for exhibition. The paintings of his children that resulted, such as First Steps (1956), Simon Martin Greaves (1958) and Anna Julia Greaves (1958), used paint in a post-Cézanne way, with colours mixed on a palette or plate dabbed on a bit at a time. First Steps is characteristic of the period, although its delicacy contrasts with contemporaneous, thickly impasto paintings in which forms were painted to suggest the weight of the subject and light used to model their volumes. First Steps was included in one of the most important international exhibitions of British art of the 1950s, Looking at People.

Looking at People toured Britain during 1955-6 and was visited by 250,000 people before travelling to Russia where it was the first show of Western art since the Russian Revolution in 1917. Initially including work by just three artists - its instigator, the illustrator Paul Hogarth, the painter Carel Weight and sculptor Betty Rae - by the time it reached its final British venue, the South London Art Gallery, Looking at People had been expanded with the inclusion of Greaves as well as Edward Ardizzone, Alistair Grant, George Fullard and Ruskin Spear. It was this expanded version of the show that travelled to Russia and was at that time one of the largest exhibitions of contemporary British art ever held outside Britain: the catalogue lists 156 works.

Spear, Hogarth and Greaves travelled to Russia for the exhibition, cutting the tape at the opening at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and speaking on Moscow Radio. In a speech at the opening ceremony, Hogarth told of the idealism behind the show: 'We have been moved by the fact that artists as well as statesmen can and are able to contribute to international understanding.' But this exhibition of British social realism received only limited support and its proposed exhibition at a second venue, the Hermitage, was cancelled.

Whilst there, Greaves also travelled through the Soviet Union under the auspices of the Union of Soviet Artists, meeting artists in each town, and visiting studios and workshops where he was able to talk freely with the artists. He also travelled to Armenia and produced a series of large monoprints which he later showed in London.

He found Soviet art to be figuratively competent to the point of slickness, but very worn and out-of-date by that time. Ilya Repin, for example, he disliked for his rhetoric, whilst recognising his confident proficiency. What he did admire were Russian icons and Andrei Roublyov's 2ft-high (61cm) figures, the memory of which has stayed with him ever since, while, in the Hermitage, works by Picasso, Matisse and Raoul Dufy made a lasting impression. Little was to be seen of modern Russian art as it was kept hidden away in the basement storage areas of the Tretyakov Gallery and other museums. This was frustrating to Greaves for he had hoped to see work from Marc Chagall's Vitebsk and paintings by Kasimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova, but none was to be seen.

At the end of 1956, the impression of a social realist context for Greaves's painting was reinforced by two extremely focused group shows at the Adams Gallery and the Piccadilly Gallery. Three British Painters at the Adams Gallery presented just Greaves, Middleditch and Peter de Francia. All but two of Greaves's paintings were studies of a baby and the others were of a pregnant woman, and 'owe their immediacy of feeling to a realist's true concern for the dignity and pathos of the human condition'.24 For Alan Clutton-Brock, reviewing the exhibition in the Listener, Greaves's 'series of pictures of babies show an advance in vigour and precision of statement; the best of these works have an undeniable if alarming vitality'. For John Golding 'the exhibition ... makes one aware of the extent to which the new English realism is becoming a conscious school ... all [three] take the same blunt, rather grim view of life, and all work on a large-scale in a direct and uncompromising technique'.

At Christmas 1956, the Piccadilly Gallery showed drawings by three artists: Greaves, Middleditch and Alistair Grant. This time Greaves presented no less than 14 drawings on the theme of maternity, gaining an ecstatic review from one of the leading critics of the day, Pierre Rouve:

This is drawing almost at its very best - an art that does not aim at black and white substitutes for luscious pigments and relies on a concision of line and candour of emotion. Here the draughtsman is what he should always be - a truth teller With an impressive economy of means and with a vigilant eye for the basic impact of his graphical idiom he avoids the twin traps of academic verisimilitude and expressionist rhetoric. Through the elimination of the superfluous he achieves that overwhelming immediacy without which drawings lose their autonomy to become mere stand-ins for a painting to come. With Greaves, drawings are stars in their own right - for his art, bred on simple integrity becomes more and more a decisive denial of artfulness.

The immediacy and clarity that Greaves now demonstrated as both painter and draughtsman owed much to what he had learnt in Italy.

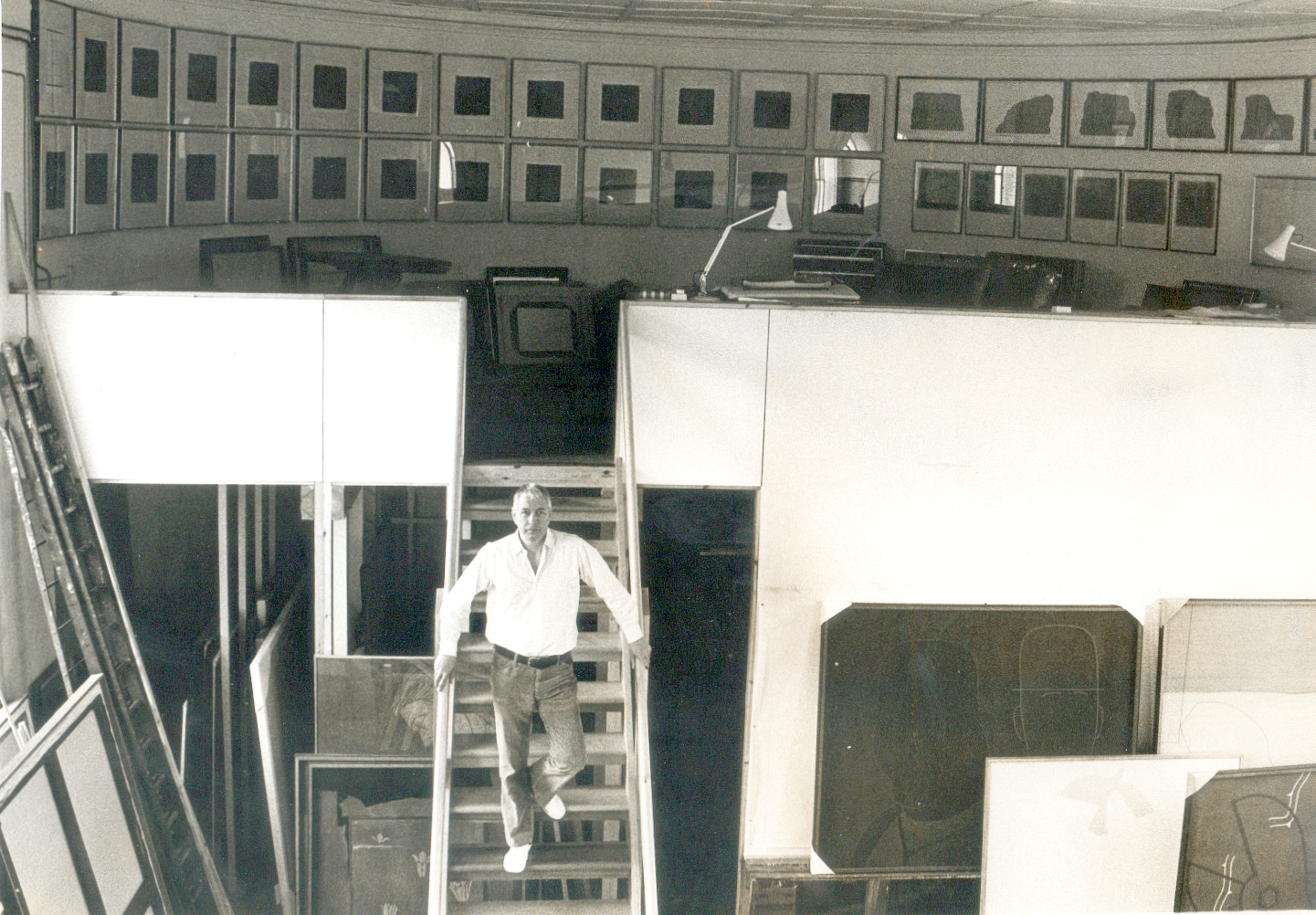

%20in%20the%20painter's%20studio%2C%20Rome%2C%201953_400x548.jpg)